By: T.D. Barnes (former E-5)

In May 1959 I graduated from the 56-week Nike Hercules Fire Control Maintenance AAA&GM class at Fort Bliss, Texas. I was selected to attend the 6-month USARADSCH Air Defense Missile maintenance class on the United States' latest air defense missile, the HAWK. I graduated in July 1960. I successfully passed the test on the Army's new proficiency pay program, which I credit for the army selecting me for a clandestine operation aboard the CIA/NSA Project Palladium ghost plane evaluating the ECM and ECCM electronics of the HAWK system against a USSR radar installation in Cuba. Shortly afterward I received notice of my deploying with Battery B, 6th Missile Battalion, 52d Artillery, the first HAWK missile battalion ever deployed by the U.S. Army.

First a bit about the HAWK missile system:

The HAWK surface to air missile system provided medium-range, low to medium altitude air defense against a variety of targets, including jet and rotary wing aircraft, unmanned aerial vehicles, and cruise missiles. This mobile, all-weather day and night system is highly lethal, reliable, and efficient against electronic countermeasures. The name Hawk, originally for the predatory bird, later turned into an acronym for "Homing All the Way Killer." The HAWK system initially fielded in 1960, provided US forces with low to medium altitude air defense for forty years. A HAWK battery consisted of missiles teamed with acquisition radar, a command post, a tracking radar, an Identification Friend or Foe (IFF) system, and three to four launchers with three missiles each. The system divided into three sections: acquisition, fire control, and firing sections. Pulse and continuous wave radars provided target detection to the fire control section for engagement evaluation. The fire control section could also receive target data from remote sensors via a data link. The fire control section locked onto the target with high-powered tracking radar. The fire control section could launch a missile or missiles manually or in an automatic mode from the firing section. Radars and missile had extensive electronic counter-countermeasures (ECCM) capabilities.

The HAWK Fire Unit was the primary element of the HAWK system. The firing battery had two identical fire units, each consisting of a command post that housed the operator console, a continuous wave acquisition radar (CWAR) for target surveillance, a high power illuminator for target tracking, MK XII IFF interrogator set, and three launchers with three missiles each. Typically, the HAWK deployed in a battalion configuration, communicating with the controlling unit (usually a TSQ-73 Missile Minder) over an Army Tactical Data Link (ATDL-1) connection as well as on voice.

6-52 Activated

The Army activated the 6th Missile Battalion, 52d Artillery on 17 November 1960 at Fort Bliss, Texas with officers, NCOs, and soldiers brought in throughout the Army to undergo basic and advanced unit training at Ft. Bliss. The battalion left the United States from New Jersey in June 1961 aboard the USNS Buckner and arrived in Bremerhaven, Germany somewhere around mid-month June. The battalion commander at the time was LTC John Tichner; the battalion Sergeant Major (the Army did not use the designation CSM then) was SGM Victor Hayward: two exceptional men and outstanding leaders. Most of the NCOs then were WWII and Korean War vets.

The Army activated the 6th Missile Battalion, 52d Artillery on 17 November 1960 at Fort Bliss, Texas with officers, NCOs, and soldiers brought in throughout the Army to undergo basic and advanced unit training at Ft. Bliss. The battalion left the United States from New Jersey in June 1961 aboard the USNS Buckner and arrived in Bremerhaven, Germany somewhere around mid-month June. The battalion commander at the time was LTC John Tichner; the battalion Sergeant Major (the Army did not use the designation CSM then) was SGM Victor Hayward: two exceptional men and outstanding leaders. Most of the NCOs then were WWII and Korean War vets.

Proof that it pays to know someone

Everyone departed Fort Bliss, on ordinary leave with orders to report to New Jersey by whatever date it was, to board the ship. I was one of the two enlisted personnel who managed to get approval for concurrent travel for my dependents. Mine was the only American-born dependents on the ship.

At the time we were notified of pending deployment, our destination was secret. Scuttlebutt had the battalion going to Leghorn, Italy. In order to take your dependents with you, you had to either have a relative in the area of deployment with whom the dependents could live, or you had to have guaranteed quarters off base. Naturally, everyone tried to meet these requirements in Italy. Acting on a tip from one of my "no-name" associates in the ECM/ECCM games we played with the USSR during my ghost flight (one completed, one aborted), I contacted a master sergeant living in Germany from whom we had purchased our home in El Paso. To make a long story short, his wife agreed to be my wife's cousin for the purpose of our applying for concurrent dependent travel.

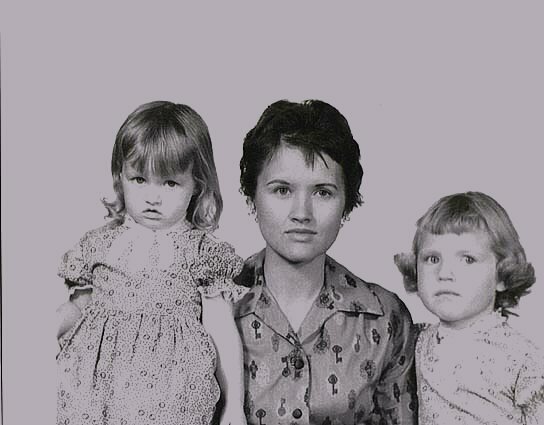

After a 30-day leave, I showed up in New Jersey with my family. We turned our vehicle in for shipping and reported aboard the USNS Buckner was assigned a first class compartment. Out of our battery, only one other family was authorized to accompany a member of our unit, SFC Sanders whose wife was from England. I recall us attending one movie during the 8 days it took us to sail to Bremerhaven. It was "Porky & Bess." The meals were as good as on any cruise ship. On occasion, we were honored to join the ship's captain for dinner at his table. Our assigned seating was two tables away and the captain honored us with his invitation, based, according to him, the ladylike manners of our two young daughters. Baby sitting our children was no problem either. Seems everyone in the troop's section was willing to do anything that gave them an opportunity to visit the upper decks housing officers and the dependents aboard. Our youngest daughter became ill on the way over, running a high temperature. She received excellent medical attendance from the battalion doctor. From Bremerhaven, we traveled to Bamberg by train, which was another enjoyable adventure for us.

Upon arrival in Germany HHB & Btry A went to Emery Barracks (also referred to as "Emery Kaserne" in Wurzburg), Btry B went to Bamberg, Btry C to Giebelstadt, and Btry D to Wertheim. The Battalion TOC was about 10kms east of Wurzburg. The Battalion was the first fully operational HAWK Battalion in the Army. At the time, we were under the 69th Arty Gp; its HQs use to be on the 2d floor above the Battalion HQs. First fully operational HAWK Battalion in the Army.

The 6-52d was the first operational HAWK Battalion in the Army. The other two at the time were still in training phase. There were no HAWK Battalions in the United States. Due to the Cold War and the Soviet threat, the priorities were Europe and other overseas locations.

Battery B billeted in a large, 3 or 4 story building with the orderly room on the top floor along with a few private rooms for billeting the NCOs. The remainder of the troops billeted in small rooms crammed with cots. If I recall correctly, we deployed the missiles in an open field northeast of the historic town of Bamberg. A paved highway passed near the missile launchers. One of our favorite past times was to use the remote control of the launchers to make the missiles appear locked on moving automobiles.

From a military standpoint, tensions were very high between the U.S. and the USSR. I recall one time our going on alert and moving into a deployment area where a 280mm atomic cannon was set up. We could count on having to arm the missiles about once a week because of an unidentified plane heading across the Czech border into West Germany. Our Air Force always scrambled to meet the aircraft and we would get an all clear as the plane crossed into West Germany. We knew that the US was no longer flying the U-2 over the USSR after the Gary Powers incident. These were flights probing our defenses.

The Berlin Crisis

Our deployment to German happened concurrent to the USSR building of the Berlin Wall. As quickly as we could, we went operational with the battery under a full-scale alert, with fingers on the trigger. As I recall, we stayed at full-alert for around three weeks while awaiting the other batteries to become operational to relieve us. For three weeks the generator ran continuously to power the acquisition radar. We refueled the generators while running. By the end of the three weeks, the bearings in the acquisition radar screamed for lubrication.

When the battalion deployed, it brought with it an inventory of missiles from the McGregor Missile Range. Ninety days after operational, my section rotated the missiles from the launchers one by one for evaluation in the test area. There, we connected them to a test unit that provided electric power and hydraulics to substitute for the electronic and hydraulic systems of the missile. These missiles upon which we had depended on for the last 90 days to protect the free world from the ugly bear, were far from being capable of hitting anything. To our surprise, we found when we opened the platters of electronic components sage brush and other plants indigenous to the El Paso area, sprouting and growing amidst the electronic components. Apparently, Raytheon had not waterproofed the seams of the access covers, which was not a major problem in the dry climate of White Sands. In Germany, however, the missiles were exposed to a wet environment which resulted in the vegetation we discovered. After that, we reassembled the missiles after testing with a waterproofing procedure. We smeared a DC4 compound into all electronic plugs and jacks, plus along every seam. We then applied duct tape over the seams and purged the interior before pressurizing the electronics area with a two PSI air pressure.

Another procedure that comes to mind was our method of obtaining desperately needed parts for the missiles and launchers. Routine parts we maintained in our supply, but for those, we didn't have, we ordered through a procedure we called "Blue Streak." Declaring "Blue Streak" meant that we needed this part yesterday and that it had better be here tomorrow at the latest. We obtained Blue Streak items wherever the source and by the first available flight.

My wife and both our children were issued dog tags and every six months participated in a mandatory dependents' evacuation run to Paris while we soldiers loaded all our TO&E property and rushed to set up operations out in the boondocks.

|

|

|

|

| T.D. | Doris | Debbie | Tammy |

Class Six Privileges

One of the perks of having dependents with you was that your liquor quota far exceeded that of single GIs. My wife and I provided the booze for many a party, usually at our small apartment and attended by all ranks, from first lieutenants to PFCs. The mess sergeant would furnish the grub from out of the mess hall.

Curfew

We also had a curfew to contend with. At 2400 hours daily all military personnel had to be off the street. If married, they had to be in their quarters. Those living in the billets had to be in their bed. Every day between 2400-0100, the CQs & Bn staff duty officer/NCO conducted a bed check. Those not in their bed received an Article 15 punishment, no questions asked!! To the dismay of our single guys, the Air Force had no curfew and could be depended on to be standing by to entertain the local girl that some Army guys had been boozing all evening.

Roughly 15-months into our 36-month tour, my participation with the CIA at Fort Bliss produced a career-changing event in our lives. One afternoon, I answered a summons to the orderly room to find two CIA officers there to recruit me to go to Vietnam as an advisor. I agreed to go under one condition, that being me a commissioned officer. Eighteen days later, my family and I were back in Oklahoma with me reporting for Officer Candidate School, OCS Class 5/62.

[an error occurred while processing this directive]